Cloud Migration Planning: A Step-by-Step Guide and Timeline

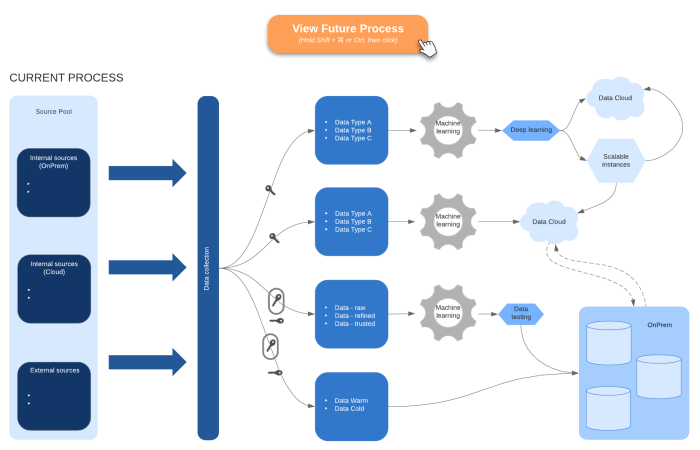

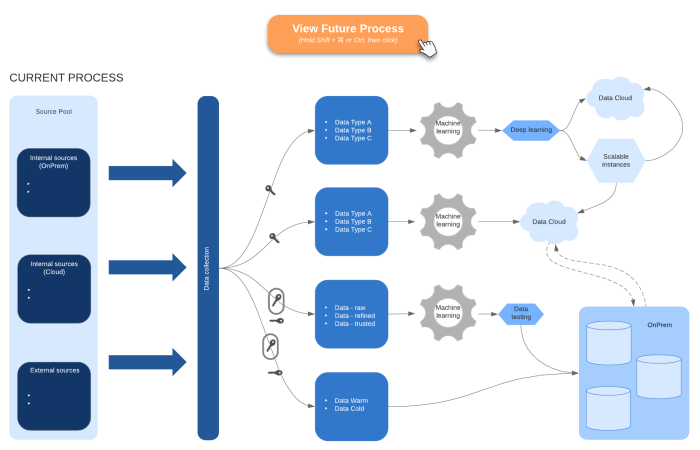

Migrating to the cloud demands a well-defined plan and timeline for success. This article outlines the crucial steps for developing a robust cloud mig...

Discover the latest insights, tutorials and expert analysis on cloud computing, serverless architecture and modern technology solutions.

Stay updated with the latest trends and insights in cloud computing technology

Migrating to the cloud demands a well-defined plan and timeline for success. This article outlines the crucial steps for developing a robust cloud mig...

For small businesses navigating the complexities of cloud spending, FinOps provides a strategic framework to optimize cloud expenses and maximize valu...

To maintain application health and optimize resource utilization within your Kubernetes clusters, robust monitoring is essential. This comprehensive g...

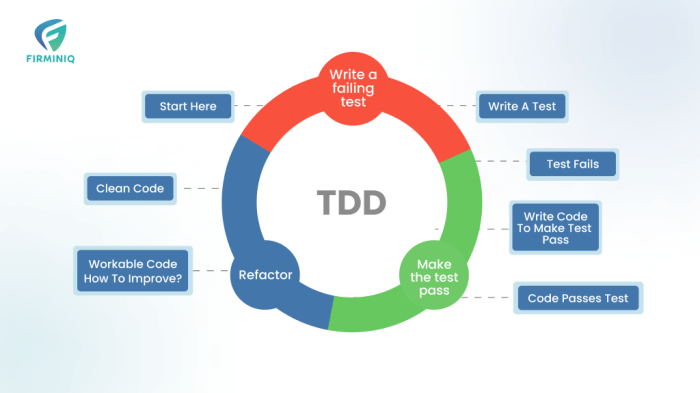

Test-Driven Development (TDD) is a software development methodology that prioritizes testing *before* code creation, a reversal of the traditional pro...

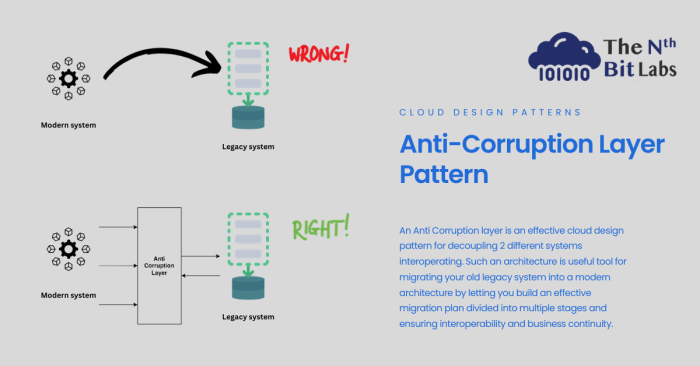

The anti-corruption layer pattern is a critical architectural approach for shielding core applications from the complexities of external systems. This...

This comprehensive guide explores the multifaceted landscape of container security, outlining critical best practices to protect your deployments from...

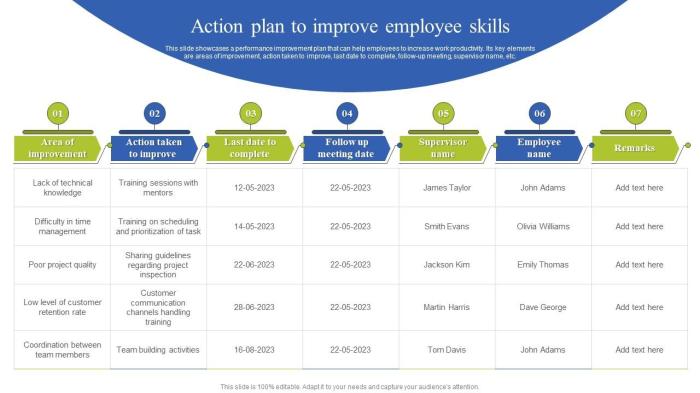

In today's evolving work environment, developing a skilled and prepared team is critical for organizational success. This guide provides a strategic r...

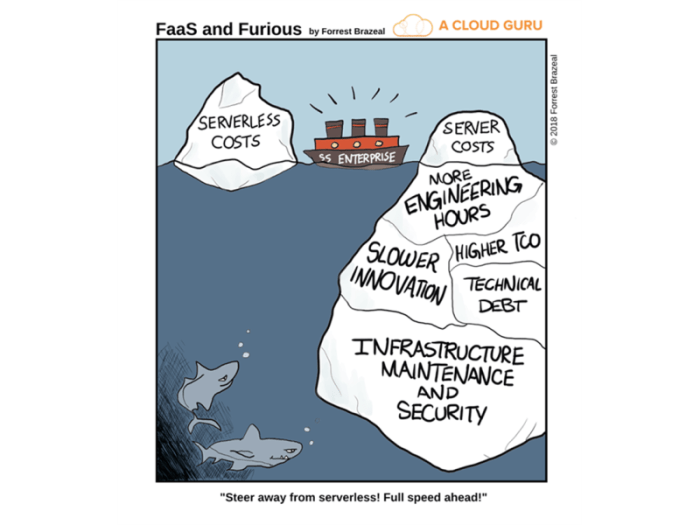

This article delves into the often-overlooked cost implications of serverless cold starts, a crucial factor in optimizing application performance and...

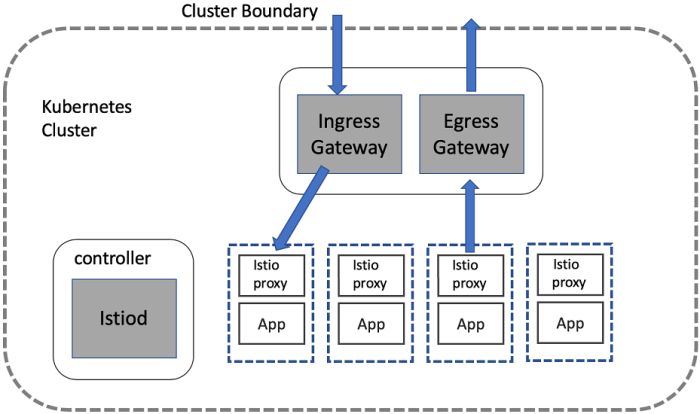

Gated egress and ingress security patterns are fundamental to robust network security. These patterns govern the flow of traffic entering and leaving...

Selecting the appropriate cloud operating model is paramount for organizational success. This article explores the significant and often detrimental c...

This article provides a clear and accessible introduction to FinOps, explaining its core principles and demonstrating its value even for those without...

In today's cloud-driven landscape, prioritizing data privacy is critical. This article provides a thorough overview of designing secure cloud architec...